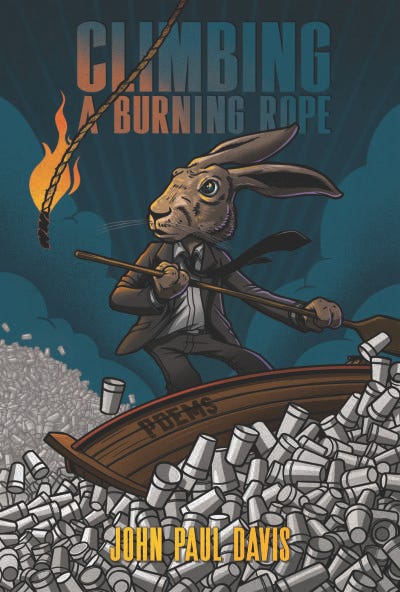

Announcing Climbing A Burning Rope

My second book, published by University of Pittsburgh Press, is out February 13, 2024

Dear Friend,

It’s raining on this Saturday morning here in New York City, the seventh Saturday in a row it has rained. I tell you, I don’t mind the rain - in fact, I rather enjoy it. Of course, nothing requires me to be out in it working; I can enjoy it as an aesthetic experience, with the skies grey and filled with dramatic clouds, the soft percussion of it on the window pane, the periodic swoosh of wet tires on the street below, a warm cup of coffee nearby, some jazz on the stereo, and my brilliant, unimaginably talented wife across the room practicing lines for an audition in a whisper.

Last year around this time, my optimism about the fruits of participating in the surreal & bewildering world of poetry publishing overcame my frustration & disenchantment with it. I have a great distrust of poetry-as-a-profession, yet I do not write to speak into the void, as it were. So every so often I push against the wind and submit poems to journals, and the current manuscript to open calls for books. I do this, and then promptly forget all about it, because the alternative would be to think about it, to get addicted to Checking The Submissions’ Statuses.

Earlier this year, in January, when my wife and I were in Cambridge Massachusetts where she was in a show (the beautiful play adaptation of Life Of Pi), I got a text from the poet Jeffrey McDaniel, who Mahira and I had run into the previous summer at Lincoln Center in Manhattan., That unplanned encounter had turned into a lovely al fresco dinner with he, his wife and dog at one of those surprisingly lovely COVID-era outdoor dining areas so many restaurants erected during lockdown when going inside a building that had human strangers in it was a terrifying prospect.

We had a lovely time; Jeff and his wife are the sort of smart, humble, generous, kind and curious people that make for great company, and we’d agreed we should Do This Again Sometime Soon. Jeff is also one of my favorite poets; his work is marked by a unique and peculiar perspective, gritty irony, unsparing self-reflection, economy of diction, a striking vocabulary, irrevenrence, but also reverence and tenderness and hope. Jeff’s poems bring forward the big common conundrums of being human with arresting language. I first heard him perform some of his poems at the National Poetry Slam in the 1990s, and went immediately to a bookstore to order his (then only) book, Alibi School.

Flash forward to the following January, and I get a phone call from Jeff, who, thus far in my life had never called me; we’ve texted or (it seems like a different lifetime, given that it’s been almost 10 years since I’ve had an account) Facebook messaged in the past. Jeff is driving as we have this call, and he’s excited about a book, telling me how much he likes the book, how it maybe needs some editing and some futzing with the order of poems, but he really thinks it’s a unique book with a peculiar-in-a-good-way perspective on work and labor, and friends,; I confess I had no idea what book he was praising. Eventually I think he realized what I did not realize and paused to say “You know I’m now an editor at University of Pittsburgh Press? You submitted your book to our call for manuscripts last fall and we’d like to publish it.”

Friend, I think the next thing I said was something profound and memorable and poetic like “oh, wow.”

For those not deeply familiar with the poetry publishing world, the Pitt Poetry Series is one of the most respected poetry series in recent history, and they have published many authors whose work I admire, including Jeff’s, but also Ross Gay, Tiana Clark, Dorothy Barresi, Jan Beatty, David Wojahn, Nate Marshall, Larry Levis, Wanda Coleman and many others. The series is so well-curated that it’s been like a trusted record label, the way Sub Pop or Def American/American Recordings in the 1990s or Stax Records in the 1960s was - you could reliably assume anything released was probably going to be great.

So I’ve spent the spring and summer editing the book primarily with Jeff, but with some input from the series’s other editors, Nancy Krygowski and Terrance Hayes, and just getting notes from poets of their sensitivity and skill has been a powerful experience.

Inasmuch as poems can be “about” something, the book is largely about what it’s like to work in our economic system and society, what Vanessa Machado de Oliveria called “coloniality modernity” and Martin Pulcher calls our “resource-extracting way of life” and what almost everyone calls “capitalism.” I began writing it when I was working for a Giant Advertising Agency - the absurdities and Kafkaesque systems of such a large company had me reflecting on my history as a worker.

Over the decades I’ve had all manner of interesting jobs, partly because when I was growing up my family was poor. Not homeless-poor or shoeless outhouse poor, but definitely below the poverty line, drinking-powdered-milk, me-wearing-hand-me-downs-from-my-sister, had-no-health-insurance, one-paycheck-away-from-distaster poor. So I had my first job when I was 12, which was a survival choice, not a pocket money choice. I had three paper routes, and what I used the money for mostly was to buy clothes and school supplies, and, often, food, necessities a 12-year-old should ideally not have to be thinking about at all. (To be clear, my parents fed my sisters and I, but I was always hungry, and so I often spent my paper route money on food).

My father got laid off for the third time in a decade when I was 15, and he remained either unemployed or working retail jobs (instead of being able to put his bachelor’s in engineering to use) until I was almost out of college. That meant that I had to put myself through college, and I had to hold down a full-time job as well, so that I could eat. When my friends were having the kind of college experience one sees depcited in film and television, I was stocking grocery shelves or waiting tables or working the line in one restaurant or another. I don’t regret it; I learned a lot from those experiences, and often, I enjoyed the work. It was also easier for me than for many of my coworkers because even then I understood I wouldn’t be working these kinds of jobs forever; eventuallty I’d graduate and enter the “white collar” workforce. It also meant that, when, after graduating college, I couldn’t find employment in the professional-managerial class, I had no qualms about finding another working class job; after college I worked for some years in such roles until I finally managed to start getting work doing something I’d not gotten any schooling for at all: desiging and programming web pages.

Over the years I’ve been a paperboy, a roller-rink deejay for Christian rock night (I’d sometimes scandalize the holy rollers by playing a track by U2 or Amy Grant or MC Hammer - Christian enough that they couldn’t fire me, but secular enough to see the youth pastor squirm out there under the disco ball), a concession stand short-order cook, a grocery bagger, a movie theatre projectionist (back when films were projected through actual film), a cater waiter, an event manager, a warehouse manager, a busboy, a dishwasher, a line cook, a delivery driver, a baristo, a writing tutor, a substitute teacher, a bookseller, a bicycle messenger, a college professor, and most recently, as mentioned above, a maker of web pages. I’ve spent the past six years writing about all of that as well as office culture.

But that isn’t the only work the book addresses. There are other kinds of work; for example, what some corners of the internet call “emotional labor” but which I prefer to think as of “good works,” (to borrow a religious term) or maybe just “love,” that is, the work we do to be in community or relationship with other people. And then there is what Ivan Illich called “shadow work,” which is the work we do in order to create the right conditions for our paid work. This includes things like commuting to an office, relating to our colleagues, learning how to select appropriate outfits, running a household such that we can be on time to work and be well-fed and well-rested to do it. There is also what I think of as “spiritual work”, which is work none of us can escape (just like all the other kinds) whether we think of ourselves as spiritual beings or not. Spiritual work is the work of understanding ourselves, our motives, learning to align our behavior and choices with our values, learning to stand up for ourselves, learning to love ourselves and others truly, not just when it feels good, learning how to forgive, learning how to let go, learning how to accept suffering when we’re powerless to avoid it, learning to accept it when we have the power to avoid it but avoiding it would cause others suffering, learning to find joy and be at peace.

The book is called Climbing A Burning Rope, and I’m pretty proud of it, and I can’t wait for folks to read it. It comes out February 13, 2024. You can pre-order it now, which, I am told, is helpful to the press as well as to the book’s ultimate success, because, I imagine, it pleases the accountants, who are happiest when the future is more predictable. If you like my poems and are plannig to buy the book, please consider doing the pre-order thing.

The cover was designed and illustrated by the incomparable Clinton Reno, whose work I have long admired.

Here are some kind things other writers whose work I admire have said about the book:

"Set in a world of quarterly growth targets, global warming, mergers and acquisitions, and neurotoxins, Climbing a Burning Rope is a delightful exercise in humanizing the drudgery. John Paul Davis centers the worker—the grocery bagger, the line cook, the company man irritated by the word learnings—in imaginative, engaging poems that defy both late-stage capitalism and a faith imposed in childhood. With wry humor and attentive wit, these poems range from ‘Ode to Not Answering My Phone’ to ‘Speaking in Tongues’ to ‘Bring Your Selves from a Parallel Universe to Work Day’ to ‘Big Data,’ in which a man cracks his skull and lines of code and timesheets pour out. Climbing a Burning Rope is a timely collection that makes a heartwarming case for love, for community, and for more poems about key performance indicators." - Eugenia Leigh, author of Bianca

"As he hunts for the gems of tender humor and humanity buried in the drudgery of our American work lives, John Paul Davis warns us, ‘In the coming utopia, there will be even more paperwork.’ Is singing the remedy to corporate work? Is marriage secretly the most thrilling ride at the fair? These are some questions I wrote down while reading. Through poems that made my face hurt from grinning, Davis reminds us—with music and sweetness and aching—that the real work of our lives, in unequivocal terms, is always love." - Caits Meissner, editor of The Sentences That Create Us

"John Paul Davis carries strange things in his pockets, some smuggled out of the wreckage of a religious childhood, others he will let loose among the screens and Post-it notes of the workplace: rabbits and horses and ancient deities and laid-off colleagues. There are poems here that testify to the irruptions of the holy into the mundane, poems that testify to the gap between belief and truth, poems that made me laugh, poems about how love and beauty remain undeniable in spite of the warming seas and the system’s lies." - Dougald Hine, cofounder of the Dark Mountain Project and author of At Work in the Ruins

"Childhood sorrows, fruitless faith, and family’s failings create in the poet a need to balance the off-balance world with poems of forgiveness and love. Little things take on meaning: shelving books in the library, bagging groceries, even clapping, “especially if we are the only ones applauding.” In Climbing A Burning Rope, redeeming acts of intimacy are more than consoling, they are seen and celebrated as holy gestures. As John Davis writes of the human embrace, “When I lay my cheek on your clavicle/you put the little rabbit of your hand/inside my shirt over my sacrum/in our theology this choreography/is the same exact thing as praying." - Richard Jones, author of Stranger On Earth

Music

The jazz I mentioned I’m listening to above is several albums by pianist and composer Carla Bley, whose work I was introduced to only last year around this time by a guitarist I sometimes collaborate with, Patrick Sheperd. Word of mouth is still way better than any algorithm for reccomendations; Patrick figured I’d like her music and boy was he right. I’m revisiting Bley’s music because she passed away this week, and something I often do when a musican I like has died is honor them by listening to their catalog. My Carla Bley heavy rotation these days is these three albums:

Sextet - Though it has that unmistakle 1980s jazz production, these tunes pull me out of my day to somewhere else every time. It was not well-reviewed when it was released, but where the critics needed to write something to pay rent, I just need some goregous music in my life. There also eleven musicians performing here, not the six the title would lead you to believe, which nose-thumbing I appreciate in the same way I appreciate that Ben Folds Five has ever only had three members. | Listen: Apple Music / Spotify

Trios - recorded with frequent collaborators, bassist Steve Swallow and saxophonist Andy Shepperd, this album demonstrates how beuatiful music can be when the players communicate effortlessly and the songs are expertly composed. | Listen: Apple Music / Spotify

Social Studies - This is the most cerebral of these three albums and cerebral jazz is not normally my favorite, but here, Bley’s talent as an arranger makes this record an adventure with a dynamic range of emotion rather than a dry intellectual statement. At moments the arrangments and instrumentaion remind me of Charles Mingus at points, Duke Ellington at others. | Listen: Apple Music / Spotify

Theatre

If you live in or near New York City, you still have a few days left to see Two Brown Porters, which is based on an unverified account of how the Koh-i-noor diamond was temporarily lost by Sir John Lawrence and returned to him by a valet. Deftly directed by Rajesh Bose, actors Sathya Sridharan and Omar Maskati bring the titular porters to life in a performance that is sometimes darkly comic, sometimes heartbreaking.

Readings

“I Was Picked Up from School on a Harley Once” by Karl Michael Iglesias is just subperb.

Here are Ted Gioia’s favorite Carla Bley songs.