Dreams and Motives

I reflect on a recent dream and answer some questions about ideas brought up in past newsletters.

Dear friend,

Last night I had a vivid dream in which I was attending, for the first time in two decades, a poetry show I frequented when I was living in Chicago in the late 1990s. At that time the show, which was a poetry slam with an open mic, was held in a bar named Mad Bar, which has long since gone out of business. In the dream this wasn’t true; Mad Bar was still there at the six-point intersection of North Ave, Milwaukee Ave and Damen Ave.

In the dream Mad Bar was still there, and it was I who had disappeared. I attended the reading but was frustrated because the bar was so dimly lit that I couldn’t see anyone’s faces, and, in the weirding logic of dreams, therefore could not truly hear the poems. I looked in vain for the people I remembered and loved from my time there, Krystal Ashe and Anacron, the showrunners, poets Marty McConnell, Tyehimba Jess, Tara Betts, Maria McCray, Kurt Heinz, Anida Ali, Dennis Kim, Marlon Esguerra, Mad Peace, Jason Pettus, Shappy, Trooper Tru, Kent Foreman, Lucy Anderton, Andi Strickland, Steph Costello, and so many others. None of them were there. No one recognized me.

This wasn’t an anxious dream; inside it, my reaction was well, this was to be expected. But it was a sorrowful dream, not because the people I once knew there weren’t there, but because the low light was keeping me from making new friends and hearing new poems.

Scientists don’t know what part of the brain generates dreams, and they don’t know what the purpose, if any, of dreaming is. Until very recently in human history, it was seen as very rational to believe that what happened in dreams was as real as what happened in waking life. Growing up in a theologically conservative evangelical family, I was taught that dreams are often messages from God. Though I’ve left conservatism in general and evangelicalism in specific behind, I’ve never felt it necessary to rid myself of the idea that the whole world is, as the poet Dante believed, saturated with communication from the divine, dreams included.

Or sometimes dreams might be communication from myself. When I first moved to New York right around the same time my ex-wife and sons moved to North Carolina, putting 500 miles between us, I had a recurring dream in which a nuclear war had happened, and I had somehow miraculously survived the attack on Manhattan, and now needed to make the journey on foot to North Carolina to make sure my sons were alive and safe. I didn’t see in that dream a prophecy of coming war, but rather an indication of my anxiety and sadness about the future.

With this one, who knows? Perhaps it’s a sign that I miss attending poetry shows, and it’s maybe time for me to get back out there, find myself a show I enjoy, where I respect and am moved by the poems. Perhaps it has come because I’m about to take a trip to Chicago to visit old friends, including a few of the people from my list above. Perhaps it’s because I’ve been toying around with the idea of starting my own reading here in New York, even though 20 years of running one reading or another in several cities has taught me that running a poetry show is a lot of hard work. I will need to think on it more. A definitive answer will never come, but dreams strike me as more like the wind than a map - they blow in a general direction, and general is often good enough.

Thank you for reading Bigger On The Inside. This post is public so feel free to share it.

I received a couple of great replies from readers this week and I decided to spend this week’s entry responding to them. The first is:

In the June 19 letter you seem to arrive at the conclusion that William Blake’s motive for writing poetry - doing it for the spiritual glory alone - is “impossible,” because we all create in order to connect with others. But in the June 26 letter, you seem to contradict this, suggesting that a healthy motive is one’s own relationship to the work and the act of making.

Firstly, I want to confess that, if it wasn’t clear already, I am feeling my way along in this project; I am partly writing these letters so that I know what I think. So I wouldn’t be surprised if I contradicted myself in the process. However, I don’t think in this case I have, so I want to take a moment to clarify.

Blake, unrecognized in his lifetime, saw his work as something done for the glory of God. But Blake, at the same time, did sell his work (it sold poorly in his lifetime; I’ve already sold 10 times more books than Blake did while he was alive), and preserved it such that his friends and family were able to continue selling it after his death. The point is that Blake wasn’t working for “art’s sake” or really for spiritual glory alone; he wanted to get his work out to the public, and tried to do so.

Part of the reason I invoked him was precisely because of this - I think his desire to have others experience his work was healthy; again, why bother making art no one will experience? Art-making is world-making, and artists want to share the doorways to those worlds. Blake was no different. At the same time, his way of making sense of the fact that while he believed his own work to be well-made, people did not seem interested (during his lifetime) and so he focused on the spiritual glory as his motive.

In other words, there are two different relationships here, the artist’s relationship to other people, and the artist’s relationship to the work itself. What I’m suggesting is a stance that mirror’s Blake’s.

Several years ago, I was attending a launch party for a musical version of Mira Nair’s excellent film Monsoon Wedding, in which my wife, Mahira, was cast, and Mahira asked me to bring along a copy of my book, Crown Prince Of Rabbits. She wanted me to gift it to Ms. Nair, and I felt quite sheepish at the idea of foisting my book, unasked-for, onto her. At the party, my wife told her as much, to which Mira replied “We must always share our work, dear.” And she happily accepted the book.

This is, I think, the healthy stance. This was Blake’s stance, despite his focus on spiritual glory. One way of looking at this is that one’s motive for making art should be focused on the work itself, on one’s relationship to the work and to oneself in the act of making it, but once the making is complete, one should not, to quote the Gospels, hide one’s light under a basket. A city on a hill cannot be hidden. The work, made, no longer belongs to us; it becomes our gift to the world.

The second respondent wanted to know more about what I described as “the (very unhealthy and largely exploitative) systems of journal publication, book contests, conferences and readings,” and why I consider them unhealthy and exploitative.

At a high level, I think they’re unhealthy and exploitative because they are capitalist markets, which flatten everything they can into products, and the process of that flattening is also a transformation, not just of what has been commoditized, but also of the people participating in the market.

I’ll use an analogy here that many of us can probably relate to: popular music. There is an excellent TED talk by the musician David Byrne about how various technologies related to recording and performance of music have shaped the music itself, and, in turn, the audiences. For example, the space in which music is performed ends up shaping the music, because certain music just don’t sound good in certain spaces. Arena rock, pop music and other genres primarily performed in arenas and stadiums tend to avoid complex rhythms and harmonic structures that contain much dissonance because the song needs to sound good and be legible in a giant room with big concrete walls off which the sound will reflect. Part of the reason U2 sound so great in a stadium, for example, is because they deliberately use echo in their songs.

This is also true of song length. Most popular music is between 3 and 4 minutes long, and that’s because the original technology for selling recordings was the 7-inch 45 rpm record, which could only hold 3-4 minutes of music per side. By the time longer media were available (12-inch records, CDs, cassette tapes), there had been decades of 45s being the only game in town, and everyone was acclimated to the idea of a song being 3ish minutes. The commodified version of songs was changed by the delivery mechanism, which in turn changed the people listening.

This kind of thing is still happening. For instance, with the advent of music streaming, royalties are paid for a song only after a certain percentage of the song has been played. The longer the song, the more seconds of it have to be played before a royalty can be paid. This has resulted in songs shifting to be shorter and shorter, but also in the structure of the songs themselves, such that there is something to grab and keep listener attention long enough at the song’s beginning. Many pop songs now start immediately with the chorus, which is usually where the catchiest bit of the melody is, instead of waiting until after the first verse.

This has resulted, in turn, with a shift in attention spans for songs; younger listeners tend to abandon a song that goes on too long, and songs with slower builds. Once again, the music was changed by the market and the listeners changed as well. Most pop songs in the past 15 years or so (since the advent of the smartphone) are written by teams of people trained to craft songs that follow one of several formulas guaranteed to catch listener attention.

I’m not here to pass judgement on the songs themselves; I enjoy some of them. But what this does is foreclose certain options for songwriters, at least if they want any hope of being heard beyond their circle of family and friends. That foreclosure isn’t simply unfortunate; it also is, as I have been suggesting, exploitative and unhealthy. It’s unhealthy because it ultimately means artists, if they want to succeed in algorithm-driven distribution systems, must behave like robots; they work “below the API,” to use Peter Reinhardt’s term. Robots didn’t take their jobs; instead robots became their managers. Here’s Reinhardt describing this in the context of Uber, but it’s easy to see how this translates to music streaming:

What’s bizarre here is that these lines of code directly control real humans. The Uber API dispatches a human to drive from point A to point B. And the 99designs Tasks API dispatches a human to convert an image into a vector logo (black, white and color). Humans are on the verge of becoming literal cogs in a machine, completely anonymized behind an API. And the companies that control those APIs have strong incentives to drive down the cost of executing those API methods.

Rob Horning makes this same point in Real Life Magazine’s most recent newsletter:

But conversely, one might also say that "artificial intelligence" simply means "disempowering workers," not replacing them, and it loosely applies to any situation where technology is employed to that end. In other words, "artificial intelligence" doesn't mean machines that can think; it means machines that facilitate exploitation. Startups, from this perspective, would tout their use of "AI" not to show some sort of fictitious form of innovation but to indirectly communicate their intention of squeezing workers as mercilessly as possible (though that would presume it wasn't already a given for any capitalist firm).

It’s exploitative for pretty much the same reasons; in the streaming era, musicians can no longer expect to make a decent middle-class living by establishing a fan base and maintaining a lifelong relationship with those fans the way that, say, Radiohead or Kate Bush or Prince supported themselves long after they were no longer delivering hit songs.

You may be thinking that this might not apply to poetry, since there isn’t a big poetry industry akin to the music industry, and while it may be true that there is no Spotify of poetry, there is a poetry industry, and it is a capitalist market, and, most importantly, algorithms don’t need computers. People can themselves be made to execute algorithms.

For example, I spent many years participating in the poetry slam, which was originally a farcical game invented by Chicago poet Marc Smith, in which audience members are picked at random and assign scores to poems akin to an ice-skating competition at the Olympics. You can still attend the original slam at the Green Mill in Chicago, where the original rules and conventions are still practiced. These rules include allowing for audience heckling of the poet (for example, women are encourage to hiss at sexism in a poem), and a madcap attitude based on the idea that the poet is beholden to the audience to connect with and entertain them. (To wit, Marc had a habit of telling poets they had to read their poem in another voice - once I had to read my Very Serious Love Poem as if I were Jerry Seinfeld, which made the poem much better.)

The slam became a national phenomenon, and, crucially, began to be used as an educational tool, and when this happened, all the madcap stuff had to go. A curriculum for children cannot include heckling. All that was left was the scoring, and pretty soon, every slam venue in the country except the Green Mill began to treat the game that had been invented to lampoon the elitism and exclusivity of the academic poetry journals with as much seriousness as that which it was meant to send up. Over time the scoring began to be taken very seriously, and within a couple of decades, the slam went from being a silly gimmicky game to being a pathway to making a living as a “teaching artist.” Where the slam in the 1980s and 1990s was an incubator for a diversity of writing and performance styles, by the 2000s there was enough of a consistent slam aesthetic that now mentioning the slam evokes a very specific image in people’s minds about what kind of literary experience they’ll be having.

The scores in this case, are literally an algorithm, but what I’m suggesting next is that you don’t even need a formal scoring system for people to enact algorithms. The slam scores, after all, were originally meant as a way of poking fun at the way the literary world already worked; they were an exaggeration of an actual system.

Actually scoring poems seems obscene in one way, an affront to how we tend to view art as being unconstrained by market forces and unquantifiable, but in fact, anywhere there is a market there is a complex algorithm. It’s not that capitalism is made more vicious or exploitative by the introduction of algorithms, but that algorithms used in this way are the logical outcome and evolution of what capitalism has always been doing. The “invisible hand” is just an analog version of “people who liked this also liked these other things.”

The poetry market, for example, is based around an academic economic model, where journals and presses are funded by grants and taxpayer dollars, which means, among other things, that the journals and presses can’t really afford to pay living wages to their workers. Most of the workers then tend to be volunteers or people who work for the exploitative deals offered by universities in which a pitiful percentage of their tuition is waived in exchange for that work.

But only certain people with the privilege to be able to volunteer or take a no-or-low-pay job in a lopsided barter with a billion-dollar institution, which means that while literary and academic publications may take great care to staff with diversity along certain lines (race, sexual orientation, gender identity, etc), they by necessity cannot staff with diversity along lines of class or education level.

Most journals and presses handle submissions by having several rounds of readers, the first tier of which are these unpaid or poorly-paid young college students (or recent graduates). This means that the majority of gatekeepers for literary presses and publications are very young people with a certain level of education and of a certain social class. This creates a system incredibly susceptible to big shifts in fashion, and is guaranteed to filter out voices that represent anyone who isn’t an academic in the professional class. It is, in short, an algorithm, just one not programmed into a computer, and it also forecloses certain options and privileges others. (It is again, also quite exploitative; graduate students are overworked and underpaid pretty much across the board. And most journals not associated with universities don’t pay their readers and editors at all. I think the Poetry Foundation pays, thanks to its big endowment, but I would be surprised if they paid the going market rate.)

So in a sense, capitalism does this to everything and always has. But just like with other art forms, since the rise of the smartphone and social media, poetry too is subject to literal algorithms, just not in a direct way. For example, clickbait sites Buzzfeed and the Gawker properties sometimes post articles about poems, but obviously only certain kinds of poems lend themselves to be treated as “content.’ In turn, journals, thirsty for audiences, have moved more and more online, participating in social media, and their gatekeepers have begun to favor works that might get linked to in an article about, say, “7 Poems To Read When The World Is Too Much” or “Answer Ten Questions To Reveal A Poem That Describes Your Personality.” (These are the headlines of actual Buzzfeed articles. I am not going to link to them.)

Again, there is nothing wrong with the individual poems, and I’m pretty sure each article contains a few that are right up my alley. But just as with Spotify changing both the structure of songs and the attention spans of the people who listen to them, as well as shifting us closer to a world where robots are the managers, so too does Buzzfeed do the same thing with writing; robots effectively have an editorial voice.

For example, poems that can be consumed on smartphones must necessarily take a narrow set of approaches in form - what is both possible with HTML and legible in a small handheld screen is all that is available. Poems that have very long lines, or use indentation or page layout in nonconlvential ways (for example, the contrapuntal poems of Tyehimba Jess which require a specific page layout) are less likely to get linked to because they don’t fit easily in a narrow text column that leaves rooms for ads on large screens and must be narrow on small screens.

Of course the poems that do get linked to and follow these new conventions are often moving, powerful poems. But they shouldn’t be the only poems possible, and writing poems that challenge or buck against those conventions shouldn’t automatically consign the writer and their work to obscurity. Similarly, the subject matter of the poems shouldn’t need to be usable as “content.” When we let markets run things unchecked, who loses out the most tends to be the most vulnerable people. In the case of sites like Buzzfeed, robots also have a growing degree of editorial input as the feedback from the algorithms tracking who clicked on what links and ads trains the human editors toward picking certain poems and avoiding others, and soon you end up with poems whose purpose it is to “describe your personality,” i.e., poems that are no different than one of those personality quizzes.

This may be just my preference, but I am much more interested in poems that remind me of what cannot be described about myself, my own mysteriousness, and the mysteriousness of the rest of the world. Poems that bring me into contact with people who are not exactly like me, that ask me to face the difficult and strange and ugly and resplendent parts of myself, and which present those same aspects of other people and the world to me are preferable to me than poems which sort me into a Hogwarts house. That sorting is just a way of training me to accept the classification assigned me by the algorithms, which are tools being used by corporate and state interests who want to make me predictable and controllable.

I see that I have not managed to keep this “snack sized.” I reckon I ought to admit now that I am long-winded, and own it.

In the vein of algorithms and publication, here are two poems of mine that are featured in the latest issue of The Antelope, whose theme was ‘code.”

Wild Life

- after Jim Harrison

Woke up full of rabbits. It didn't hurt

but with them burrowing

& flashing quick like they do all within me I was restless

in meetings & had an alertness & inner trembling

but also could feel how the natural world

had a hook in me & tugged at me & I saw my colleagues

for the giant primates they are you know

not too long ago humans were running barefoot

on the savannas & smashing the skulls

of rabbits & each other with rocks & communicating

only with grunts & gestures & casual violence

& with these gentle herbivores swimming

all around in me I can smell the adrenaline

rising in Michael & Tim when Sam the Java developer

refuses yet again to alter any of his code

to make things work a little more smoothly

for them but no matter how hardheaded your colleague

is, the shareholders need us to not murder

each other for the sake of meeting our quarterly

growth targets plus death is a bit of a harsh sentence

for being stubborn or possibly lazy

& Sam has his redeeming qualities

though with all these rabbits inside me I can't sniff

out what they might be but I do smell

everyone’s wishes as if I were the stepchild

of a forgotten god, they sing like tinnitus

in the silky long ears of every rabbit zooming

around my bones, even certain lies

are really prayers & those ring in my nose

too, people wanting raises or for insurance

to cover whatever will cure their joint pain

or their spouse to finally say what’s bothering

them or to wake up with a better president

or Michael & Tim just wanting Sam to be helpful

for once, they all commingle

& merge like the scent of a great meal

or the afternoon spring wind caroming

off the chop of the Hudson & also the racing

of birds from power lines to tree to window ledge

& yes leafy greens & buried root vegetables

let us go now, & work them out of earth

& feast on them until we are so full we sleep a sugary sleep.

Big Data

Getting back up from plugging in an electrical

cord from under my desk I crack my skull

& out of my head comes 10000 lines of code

but all discombobulated & also 5 years of timesheets

& functional specs as well. It's just like the time I spilled

coffee all down the front of my shirt first thing

in the morning & had to buy a new shirt

which everyone complimented all day

only I don't have the option of buying a new head.

After the specs pour out every email

I've ever written even the ones I regret

sending & drafts I knew better than to send

& it's becoming quite a mess on the polished

concrete floor so much so my colleagues sneak stares

& a few ask if I'm ok. Nate, who is kindhearted

& knows where the office keeps everything shows

up with a mop & bucket but data doesn't absorb

easily into cloth so he tries sweeping

it however data is light as dust and scoots

into an even wider area just from the wind

of the broom's motion. I press a small hard drive

to the gash in my temple & walk to the men's locker room

which nobody uses because we never got the promised

gym & showers & whatever bits of client intellectual

property I've known over the years starts to gush

out so they send in the lawyers with big 5 gallon

buckets to just catch it & avoid a scandal.

A doctor shows up & makes worried noises.

He's lost a lot of data, the doctor says so they haul

in monitors & show me anything they can, clickbait

& tweets & gossip, fake news & movie spoilers

meanwhile I'm still an information geyser

only now I'm gushing state secrets

I didn't even know I knew so the NSA

shows up in dark sunglasses & consult the voices

that simmer in their earpieces. They fly in some physicists

who confirm the suspicion: it's not just a leak

in my head but the universe itself; if I can't be plugged

up, bandaged or sutured all the information

about everything will flood out of me & fill

up the world because of course there is more information

about everything than there is actual everything

& at this point the company realizes they should change

their business model & start selling scoops

of the data for a premium so they clamp a hose

to my face to direct the information to a vault

which is why I will have to miss the reading of April's

play & Thanksgiving dinner & I should sell

those St. Vincent tickets because I can't leave the office

will all this company property splashing out of me but on the upside

I know at least as long as the information continues to stream

out of the growing rip in my flesh

I am never going to be unemployed.

Readings:

I find Maged Zaher’s surreal poems compelling; his sense of humor, his knack for striking and memorable phrasing (“Not every angel is terrifying”) and his honesty about his own complicity in the situations and systems his poems grapple with remind me of both Frank O’Hara and philosopher Timothy Morton. Here are six poems of his from the Capilano Review.

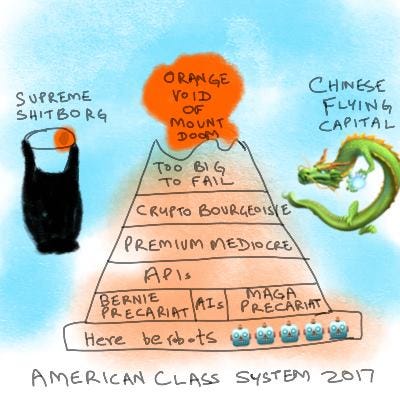

I came up the above-mentioned Peter Reinhardt’s article when it was linked to in Venkatesh Rao’s article “The Premium Mediocre Life Of Maya Millennial,” which I have returned to multiple times since I first encountered it in 2017. The article is worth it for this infographic of the American class system:

Once again I am recommending Real Life Magazine’s newsletter; especially the July 1 installment, which I quote above.

You might like Shira Erlichman’s newsletter. Shira is an excellent poet and musician, who apart from sending regular dazzling and spiritually honest newsletters about creative life, also teaches one-on-one and group classes in writing and creativity. It was Shira’s one-on-one creativity class that gave me the courage to consider myself a musician.

Music:

Speaking of Shira, this is an Instagram post of a just-written gorgeous song that I hope will get recorded and produced soon.

If you have not heard Ibeyi, go now and check out their catalog. All three of their albums are excellent. The songs are built around Naomi Diaz’s cajón and batá with Lisa-Kaindé Diaz’s piano and lead vocals, blending hip-hop, jazz and electronica.

I’m going to plug my own band’s latest single here - “Mira” is a song about the inflection point when a single choice has a powerful and lasting impact on one’s life, inspired by a talk given by Dougald Hine, and “Seaheavy” is about letting go of anger. “Mira” is also the first song I ever composed on the ukulele. (Bandcamp | Apple | Spotify)

Watch:

I stumbled on this video of Outkast’s Big Boi in a 2018 installment of Pitchfork’s VERSES series, in which rappers identify and discuss their favorite verses by other artists. In this case, Big Boi pretty much ignores the question and instead describes his favorite song, Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill,” which this summer has become a Billboard hit in multiple countries, thanks to its use in season 4 of Stranger Things. Just watching Big Boi nerd out about the song, and lip-sync the lyrics like an uncool teenager made my day - the delight he’s taking in the song is infectious, and it’s a source of joy to me to learn musicians love songs completely outside the genre of their own work.